Paradigm shift in architecture: Pharaoh, Mesopotamia, Persia is the fourth article of a series1,2,3 of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous three articles, I have discussed several different papers for academics, researchers, and professionals who have different perspectives on the paradigm shift in architecture.

These papers and research introduced various concepts such as the way firms prepare architecture , the tool used (BIM), and its effect on the final product and architecture work environment. In addition, used methods have changed and that paradigm shift happened, for instance, the parametric design method. Also, the effect of scale on the way architecture, and landscape design preparation thus a change evovlved. Finally, changes in socioeconomic and political views had an effect on the urban design field and the preparation of an urban development plan. You may want to read my discussion in the previous three articles to link ideas and discussion in this article.

This article is the beginning of my investigation of the reality of the paradigm shift, its effect on the work environment, and its real characteristics. Here I will start as indicated in my previous articles from ancient history to modern-day’s architecture. Three architectural periods from ancient time is the subject of my discussion here the pharaoh, Mesopotamia, and Persian architecture.

These architecture have initially some commonalities, surely in terms of the type of architecture that existed at the time of constructing it in the specific country. The commonality comes in terms of the major buildings being of the religious type. And as per Banister Fletcher1they affected each other in terms of thinking and doing architecture.

Paradigm shift in architecture: Pharaoh, Mesopotamia, Persia. The pharaohs

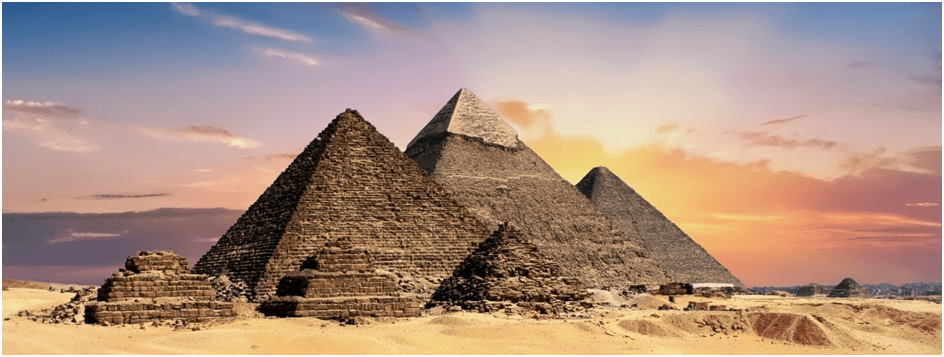

The first part of this article investigates the pharaoh architecture or ancient Egyptian architecture. This architecture is a religious type including the shrines of kings, tombs, temples, and very less dwellings. The dominant part of this architecture is the pyramids. Pharaos constructed pyramids to honor the pharaoh king in his journey to the second life. They designed the shrine in a typically form of a rigid rectangular pyramid constructed of stone. An entry exists in one of the sides to a grave box containing the king’s dead body.

On one of the other sides, a hole appears to bring light to the real location of the king’s body. Indeed, these types of architecture represent simple architecture and include limited character because of its simple form and the use available construction material in the area. Certainly, the Egyptian builders, as there were no formal architects at that time, of these pyramids’ architecture continued to construct the same type without any changes for many years till the great Roman Empire approached Egypt. See figure 1

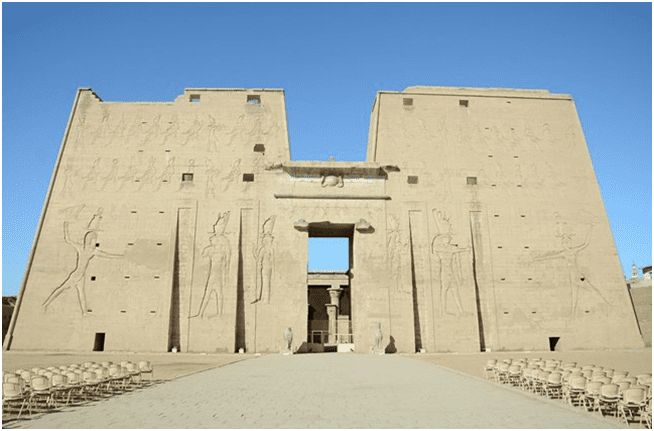

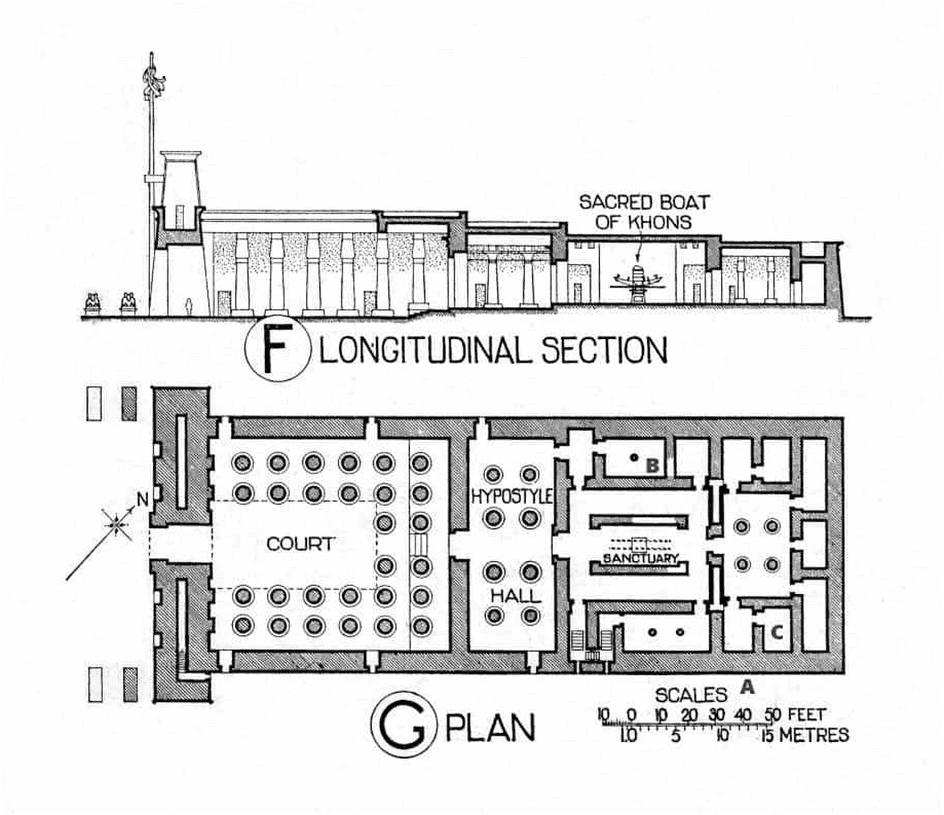

For temples, architecture does not differ from pyramids. All temples consist of three parts: the gated inclined wall entrance (see figure 2) with carving and human-style ornament, where behind it lies the main courtyard with lotus columns and arcades. The second part includes the hypostyle hall, mainly covered, and light comes from openings from two sides. The last part includes the sanctuary, the holy place location. Pharaohs built these temples only for the presets and the king to worship, and no public can access them, see figure 3 temple plan.

Dwellings in pharaoh architecture are houses consisting of the front garden and main arcade in the middle of the house, leading to the other rooms. Additionally, at the end is the staircase leading to the canopy and the second floor. Because the Pharaohs built these dwellings from mud bricks, they have vanished. Presently, no one has found any trace of them, but only drawings from previous archeology findings in the Paris Museum.

Widely known in history and academic writings that pharaoh architecture includes mainly tombs and shrine architecture. Moreover, presently no writings or archaeological findings of cities or ancient towns that describe that period’s architecture. The lotus column, used widely in the temples and shrines architecture, represents the main characteristic of the architecture. Therefore, this architecture is significantly simpler in all components. The builders focused on showing the dominance, power, rigidity, and stability of forms and shapes that make up this architecture.

Paradigm shift in architecture: Pharaoh, Mesopotamia, Persia. Mesopotamia

Mesopotamian architecture is located between and around the two rivers of tigress and Euphrates in Iraq. Here this type of architecture comprises homes, palaces, temples, and cities.

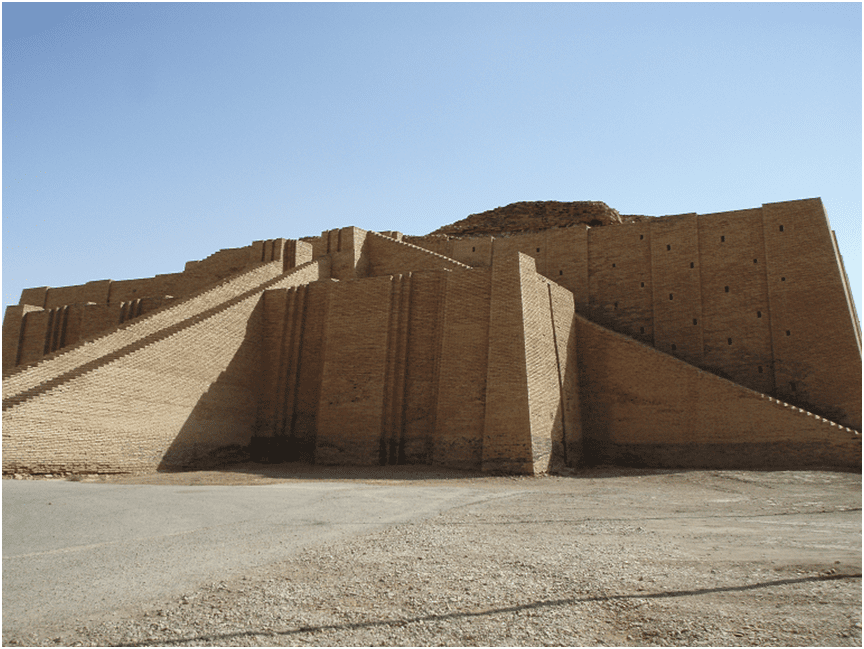

Jane 2 shows that at the beginning of religious practice temples were built to worship a god, the temple is built on a platform with adjacent rooms. In addition, in later stages, temples were built on three platforms (see figure 4). The significant change came when the people beliefs changed and the gods became humans. Surely, the temple became the home of the king’s family and dramatic change in the form of the temple and surroundings appeared.

The temple architecture became the king’s family residence including all related people’s residences as well. Specifically, the temple design included rooms for the family, halls, dining areas, food preparation, stores, and living rooms. In addition, there is no evidence why the temple was made of platforms, and the 26 temples were built some were square in plans and others rectangular.

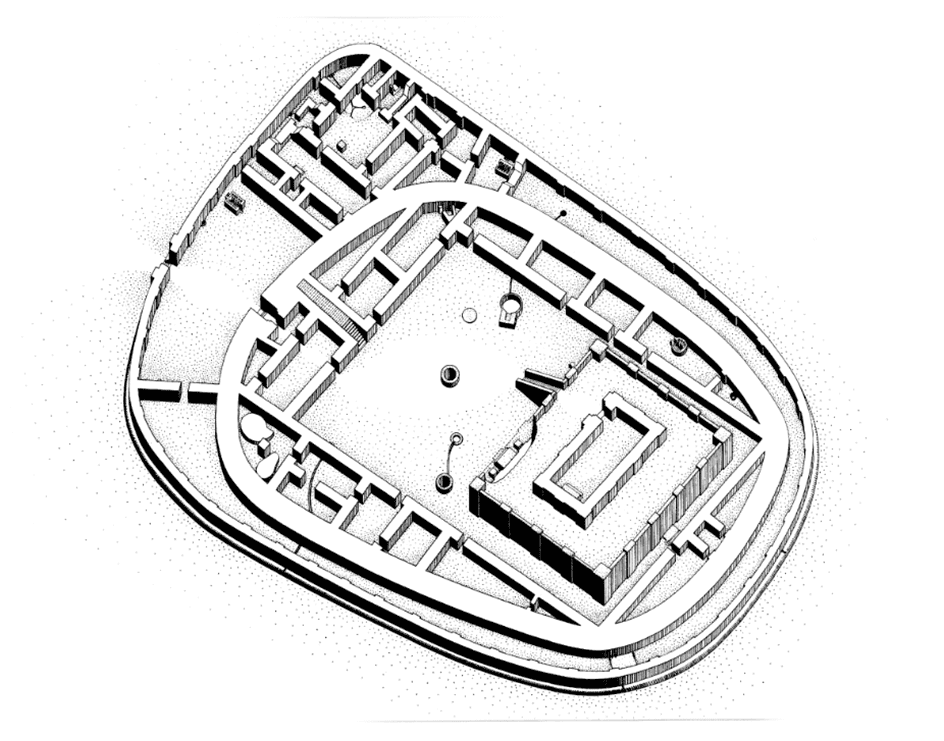

A number of different forms of temples appeared in Uruk (Sumerian period) as the Oval temple Khafaji (See Figure 5) where this temple is constructed of two platforms and surrounding rooms. The temple was not placed in the middle of the city as in other cities but at the edge of the city of Uruk.

Palace architecture main features are the compound walls and its ornament of glazed brick. The architecture of the palace is built of several courtyard themes and surrounding rooms and halls. All the palaces built in this type of architecture are similar in form and plans.

Public houses are of very simple shape and made of brick, wooden framed roofs, and mud. As for architecture, the plans are inward-looking rooms around the main courtyard and in some big homes multiple courtyards. The main feature here is the 90-degree turn of the entrance to give defense orientation and privacy.

From this concentrated text about Mesopotamia architecture, I have provided two factors that affected the architecture’s form and function. First, discussing the matter of the raised temple the change in beliefs affected the form and function of the temple architecture. When the gods became humans, they have to be located in a building that differs from the public buildings that’s why the three platforms appeared in temple architecture, and when the temple became the home of the king and the ruler family there where a need to give more impressions of power, dominance, and value. The temple surroundings became larger in scale and surrounded by a big, gated wall.

The second factor is that because the ruler is the dominant part of the city and the center of all interest in the city in terms of authority this made architects locate the temple in the center of the city. In other areas in the Mesopotamian area, people found that the temple location is not necessarily to be located in the middle since the temple has its own double gated walls. These double-gated walls give it the same dominance, power, and value.

Paradigm shift in architecture is concerned with a fundamental change in doing architecture or the way of thinking about architecture. As illustrated here in the Mesopotamia era the change in religious beliefs had a powerful effect on temple architecture. Temples started to appear as one platform then three platforms in many areas. The Temple form was mainly rectangular but, in some areas, it was square as the hanging garden temple in Babylon. After a period of time, the temple shape appeared in a very different form as the oval temple Khafaji and its location to the boundaries of the city.

Persian architecture is located to the east of Mesopotamia. As Bell 4 and Fletcher1 indicate that this architecture does not have an area character. The architecture of Persia is mainly affected by the Egyptians, Greek, and its neighboring Mesopotamia. Much of its architecture was built by Mesopotamia rulers and palaces, homes and temples carry the same characteristics. In later stages when the Persians entered wars and conquering to Greek, Egypt, and Mesopotamia their kings and conquerors carried with them the style, taste, and character of the invaded countries’ architecture. It is evident that Egypt’s effect on the construction of some temples like the tomb of the great Darius King (see figure 6).

The Palace of Darius is another example of the shared character of its main architectural elements as Greek architecture. The columns and the ornament on the palace walls carry the same impressions of Greek architecture and styles. Still, the Persians had their artistic work in sculpture and wall carving that came from their cultural and heritage practices.

In conclusion, I have discussed here three areas in architecture, Paradigm shift in architecture: Pharaoh, Mesopotamia, Persia. The only architecture that showed evidence of influence by social character is the Mesopotamian architecture. Therefore, Mesopotamian architecture has introduced a paradigm shift. If you have another point of view, you are welcome to leave a comment.

References:

- Fletcher, B. (2012) A history of architecture on the comparative method. United States: Nabu Press.

- Mcintosh, J. (2005) Ancient Mesopotamia: new perspectives. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Abc-Clio.

- Pinhas Delougaz (1940) The Temple Oval at Khafājah. Oriental Inst Publications Sales.

- Bell, E. (1924) Early Architecture in Western Asia.

[…] shift in architecture: Greek, Roman, Early Christian is the fifth article of a series1,2,3,4 of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous four articles, I have […]

[…] shift in architecture: Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic is the sixth article of a series1,2,3,4,5 of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous five articles, I […]

[…] shift in architecture: Indian-Chinese-Japanese is the seventh article of a series1,2,3,4,5,6 of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous six articles, I […]

[…] shift in architecture: Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo is the Ninth article of a series1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 .Articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous eight articles, […]

[…] shift in architecture: Art Deco, Bauhaus, De Stijl is the Eleventh article of a series1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous Ten […]

[…] shift in architecture: Modern Architecture styles-2 is the fourteenth article of a series1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the […]

[…] shift in architecture: Modern Architecture styles-1 is the thirteenth article of aseries1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous […]

[…] in architecture: Neoclassicism, Eclecticism, and art Nouveau is the Tenth article of a series1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous Nine […]

[…] shift in architecture: the Islamic world is the eighth article of a series1,2,3,4,5,6,7 of articles investigating the paradigm shift in architecture. In the previous seven articles, […]

[…] shift in architecture: criteria-character-practice is the end of this articles series1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 after investigating architecture from ancient times to the 20th […]