Urbanism: gentrification towards modern political governance is the sixth article assessing the dialectic of architecture and urban design in the urbanism field. I will go through this relationship from the top scale of urbanism in the city to the smallest scale of urbanism components of urban space.

In this article we are going to analyze one of the main concerns of urbanism is the social context of a town, neighborhood, and city and its effect on the way of life of the inhabitants. As we have notified in my previous articles that urbanism topics vary depending on the discipline studying it or conducting work in practice. Here gentrification, which has been in the academic circle and practice for a long time, is an urban activity aimed to improve the socioeconomic of an area.

Glaster1 indicates that the term gentrification has different definitions one of which is the Others see it in terms of a substantial replacement of a neighborhood’s residents who are of lower incomes by those of higher incomes. Patric2 provides a different definition of the term, Gentrification represents an important aspect of the transformation of socio-demographic structures in many cities around the world. In other papers, he defines it as gentrification has long referred to the physical

And the social transformation of central areas through rehabilitation of existing housing stock and population displacement by more affluent households, the concept has recently been extended to include new high-status developments (regeneration of brownfield sites or demolition/reconstruction of existing Residential areas). Paul3 says that Gentrification refers to the transition of property markets from relatively low-value platforms to higher-value platforms under the influence of redevelopment and influx of Higher-income residents, often with the spatial displacement of original residents and an associated shift in the demographic, social, and cultural fabric of neighborhoods under its Influence.

Gentrification is a strategy used by state or political authorities to develop a neighborhood not specifically building development it’s either buildings, social, economic, or political. Shenjin4 indicates that gentrification has been ever coupled with capital market processes, public sector privatization schemes, globalized city competition, welfare retrenchment, and workfare requirements, the process of globalization, inner city as well metropolis development, and many other threads of the fabric of neo-liberal urbanism.

Gentrification is linked with the new trend of neo-liberalism. The political approach and movement favor policies that promote free-market capitalism, deregulation, and reduction in government spending.

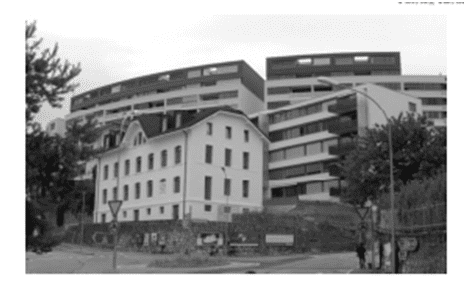

Political authorities or their representatives use this strategy for several reasons. For example, in China before the 1945 era political approach for development and its recent decline and deprivation, the previous low desirable allocation of development in a city. In the European context especially in Switzerland, the trend is reversed. The Swiss city witnessed a large shift of population to the suburban 10% because of quality of life. The cities in Switzerland’s core centers population declined. Gentrification to core city centers of Zurich, Geneva, Basel, and, to a lesser extent, Lausanne, where areas with a strong urban character have gained attractiveness. Youth of the middle class shifted and saw the core areas are more desirable for living. See figure 1.

In the same manner in Shanghai, the state and government gentrification of the city core led to the shift of a lot of middle class from various skills like administrative, and associate professionals to the center. The gentrification process of Shanghai led by the Chinese state increased the population displacement to the outskirt by 30% within 50 years. The shift of population is from low-income people. The state succeeded to conduct this gentrification because these people are living either in publicly owned housing or flats and the others are allocated by the government in a percentage of 96%. Before the gentrification, it was rare to find people living in privately owned housing. The state succeeded also because the development is owned by the government and the land also. The existing land is Brownfield, deprived industry and water frontage. On the other hand, the shifted people, none voluntarily, shifted because the state built large size housing (area) to attract these people to move to the outskirt. This gentrification has its impact on shifted people in the suburban we will highlight in a later paragraph.

The gentrification in Shanghai is similar in approach and methodology conducted in many Western cities. The gentrification has cleared out shabby housing from the core city, and old non-maintained buildings, rehabilitated Brownfield land. The state has succeeded to build massive modern apartment blocks, mixed-use districts, and green space built in central areas. The aim was that the state Endeavour to create an image of modern and civilized urban life in the core city center of Shanghai.

The gentrification of Shanghai (see Figure 2) case implies a displaced population and the city itself. The unemployment rate has massively increased and many of shifted population lost their job or quit their work. In the new outskirt because of the lack of employment, they were forced to rent part of their housing to earn their living or work in lower-income jobs.

Many of the people, who were interviewed, as shenjing4 indicate, not only lost their jobs. The displaced population lost the social network they already built for 50 years; many were shifted relevant to their fiscal capacity to different areas of the outskirt of Shanghai. Families who were taking low-income salaries in the newly displaced housing could not afford to pay for travel by train or underground. Adding to that their children were forced to keep their ties to schools in Shanghai to manage entry to university and they were attending schools only one day a week.

Gentrification comes in favor of some of the population and against the other part of society regardless of the social benefit they receive from government networks.

The new areas where people are shifted appeared with a low quality of life, pockets of poverty, social segregation, and low levels of public services.

After assessing the gentrification strategy adopted by governments in the world and political authorities, I have reached various conclusions.

I am skeptical about the aim of regeneration and its neo-liberal agendas of liberating the market. Now why shift the middle class to city centers and low-income people to the outskirt?

Cities that witness various defects in containing proper industry fail after a short period or longer. Many industries located based on short-term plans fail to gain continuity and fail to keep its operation either a lack of customers, high cost of production due to unplanned and unmanaged resources, lack of qualified skills, wrong marketing and sales procedures, and the rise of competitive product in the market with more competitive prices. These lead to the decline of many types of industries and do not receive attention from the government but only after a long period. This leads to deprivation in the area and the shift of skilled labor to other competitive areas in the city or adjacent. Many public housing units get affected and gradually become unsuitable for living. This means that the government and related planning authorities failed in aligning proper urban planning strategies and procedures for the city. The alignment of industries was not studied well and led to the decline of many of them. That require revisit to the political governance related to gentrification.

For that gentrification in reality means the redistribution of industry in a city that fits the political agendas, economic policy, and social needs like employment, housing, education, quality of urban space and landscape, and proper access to public services.

This is one of the main purposes of gentrification as I have assessed.

Another doubt I raise here is about the main aim of gentrification shifting the middle class to the center of cities and low income to the boundaries. This strategy is aimed to pump in cash flow to the city and bring people who can raise the tax paid to the government and can pay the public services cost those low-income people cannot only after obtaining government support which puts a lot of loads on public funds. Having lots of low-income people in the city core damages the government funds for the public services provided and public transport will be unbeneficial.

In analyzing this matter more intensely I have concluded that the main problem here is Land price.

Through the years while the city declined in industry and the increase of low-income people paying low taxes, public services are provided but received low cash flow, public transport become unbeneficial due to the characteristic of the population in the city, and here the land price increase dramatically that makes the government take action immediately to pump money for development. Land price increase and the low revenue of development on top of it is the main cause of gentrification.

Governments need to revisit their political governance related to a city from time to time. This is to align it with the global market trends and directions. Locating proper land use and industries that could survive or at the very least could develop when required with the help of public bodies or private investors. Analyzing and preparing market studies for land prices is one of the main tasks that protect public funds and cities from declining.

Finally, architects need to consider, within the gentrification process, what will the low-income people need when they are shifted to other locations in the city. The architecture of homes, housing, and apartments needs to be simple and affordable for this class and will not exhaust their income if they rent or if they buy. Conversion of these is easy I mean that a family could convert part of the home for rent to others. Part of the home is to build commercial units to support their income. Homes and apartments must be in a variety of sizes in reach to all levels of low-income people. Poor people can get a flat or a home that suits their income and so on.

Urban designers need to consider many issues for the new development. location of the development should be in access to affordable transport and near employment sites. Services available to provide similar quality of life provided for high-income and middle-class people. Infrastructure like schools and hospitals are available for these people and does provide good service. Building diversity means that all buildings have a variety of sizes that a low-income person could buy or rent. Commercial areas, and mixed-use development, are available to provide a chance for these people to access jobs. Urban designers when building a development strategy and plan to give more attention to land uses and provide a wide range of choices for development for different kinds of industries.

Many buildings for example can move a place towards providing jobs like a hospital building. To illustrate how this impacts the employment a hospital needs, doctors from different specialties, nurses, x-ray specialists, laboratory workers, pharmacists, maintenance people, cleaners, keepers, guards, security, and so on. Industries that support this development like all plastic products, chemicals, plastic dresses, gloves, and so on. People need transport public and private that low-income people can buy and use for transporting people like taxi and others. Food providers, restaurants, cafes, and others.

changing political governance from communism to neo-liberal has lots of implications not only on low-income people but all society.

References:

- Galster, G. and Peacock, S. (1986) ‘Urban gentrification: Evaluating alternative indicators’, Social Indicators Research, 18(3), pp. 321–337. doi:10.1007/bf00286623.

- Rérat, P. et al. (2009) ‘From urban wastelands to new-build gentrification: The case of Swiss cities’, Population, Space and Place, 16(5), pp. 429–442. doi:10.1002/psp.595.

- Rérat, P., Söderström, O. and Piguet, E. (2009) ‘New forms of gentrification: Issues and debates’, Population, Space and Place, 16(5), pp. 335–343. doi:10.1002/psp.585.

- He, S. (2009) ‘New-build gentrification in central Shanghai: Demographic changes and socioeconomic implications’, Population, Space and Place, 16(5), pp. 345–361. doi:10.1002/psp.548.

- Rérat, P. and Lees, L. (2010) ‘Spatial Capital, gentrification and mobility: Evidence from Swiss Core Cities’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(1), pp. 126–142. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00404.x.

Be First to Comment